BEYOND THE BATTLE

This year’s Presidents’ Day reception drew our largest crowd yet. Guests enjoyed conversing over wine and cheese and listening to a talk by University of Maryland Archivist and Curator, Doug McElrath about what was happening at the time of the War of 1812 in Bladensburg and surroundings beyond the infamous battle for which it is known. Mr. McElrath highlighted interesting bits of information unearthed as part of the Bladensburg History Project, which he directs. The aim of this project is to recover the Town’s forgotten past and help restore its reputation as a “place that matters.”

Reaching back, McElrath explained that Bladensburg rose to prominence as a colonial seaport in the mid-18th century, trading tobacco for finished consumer goods, mainly with Scotland. But the town had to reinvent itself when the War of Independence disrupted the trans-Atlantic trade, and the Anacostia river silted in. Helped by its location at a crossroads between Georgetown, Annapolis, Baltimore and Alexandria, and its proximity to the emerging national capital, the town was able to adjust to a new economy based on grain production and manufacturing.

In its heydays, said McElrath, Bladensburg was a regional center for businesses and services.1 There were stores, warehouses, wharves, grist mills, forges, gunpowder mills, a blanket factory, tannery, as well as tradesmen such as carpenters, shoe makers, saddlers, tailors, among others. And there were a fair number of inns and taverns to serve the steady stream of travelers. As a place of business, the Town provided opportunities not only for people in the mainstream but also for those on the margins, including African Americans, to make an independent living. One example was a Margaret (Peggy) Adams, an African American woman, who owned land, ran a tavern and had connections to important businessmen of the day. George Washington, a frequent visitor in the town, stayed at her inn and reportedly recommended it as the “best-kept house in Bladensburg.”

Mr. McElrath had more surprising stories, including an Ode to Education composed by schoolmaster Samuel Knox of the Bladensburg Academy, and recited as an elocution exercise by his pupils in December 1788. McElrath intends to publish a paper on the subject and discuss them at a symposium on October 11. He concluded by extending an invitation to attend the symposium and see an exhibit on historic Bladensburg opening at the University of Maryland in October 2014.

¹ Doug McElrath’s blog “Beyond the Battle – Bladensburg 1814“

Welcome to the home of the Berwyn Heights Historical Committee. Please feel free to provide feedback or attend one of our regular meetings on the 4th Wednesday of each month in the G. Love conference room located at the corner of 57th Avenue and Berwyn Road.

RESTARTING BERWYN HEIGHTS

On May 6, 1906, the real estate section of The Washington Times featured Berwyn Heights on page 1, 3 and 8, including a full page advertisement offering properties for sale. Quarter acre lots were sold for the price of $250, inclusive a $100 equity in the Berwyn Land & Manufacturing Corporation, set up to develop the subdivision. Berwyn Heights, with its convenient access to Washington D.C., was described as a money making suburb because investors would benefit from both, the certain increase in property values and an increase in dividends. The write-up seemed to work: one month later, a notice in The Washington Times thanked the paper for helping to sell 170 lots in Berwyn Heights.

The ads and notice were placed by former Congressman Samuel S. Yoder, who had recently purchased the holdings of the Jacob Tome Institute in Berwyn Heights, comprising about 275 acres or about 2/3 of the all the available land in the Town. Jacob Tome had financed the real estate dealings of James E. Waugh, one of the original developers of Charlton Heights, and after his death, Waugh’s properties passed to the Institute. Among the Tome properties Yoder acquired was the Waugh mansion on the eastern edge of Berwyn Heights, which became his country home.

Yoder’s purchase of the Tome Institute lands and the creation of the Berwyn Land & Manufacturing Corporation were part of a larger plan to profit from the tremendous expansion of Washington that occurred in the first decade of the 20th century. City people were flooding into the suburbs looking for affordable homes. The Berwyn Land & Manufacturing Corporation was intended to finance improvements in the subdivision to make it more attractive to prospective home buyers. But it was also meant to promote industry that made use of raw materials available in the area. Brick, tile and cement block factories were on the drawing board to supply the construction trade in the booming Hyattsville region.

Another part of the plan, was to build a streetcar, the Washington, Spa Spring and Gretta Railroad (WSSGRR), east of the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad that would serve Berwyn Heights proper and several communities on the way. Streetcars were the principle means of transportation in the city before the arrival of the automobile, and made it possible for the middle class to relocate to the suburbs while continuing to work and shop downtown.

So far, this process had largely played itself out in the areas northwest of the District, but by 1905 growth was shifting to the east of Washington, where Hyattsville was becoming a regional center of industry and commerce. Prominent citizens in and around Hyattsville joined with Yoder, who lived in the District, to organize WSSGRR. They owned land, ran businesses, held leading positions on the Hyattsville City Council and in the government of Prince George’s County and the State of Maryland. In light of the fast growth of the area, a streetcar connection from Washington to develop the “neglected” areas east of the B & O Railroad appeared to make sense.

PRESIDENTS’ DAY 2014

For the BHHC’s February 16 Presidents’ Day reception, Prince George’s County Historian Doug McElrath will give a presentation about the Battle of Bladensburg, entitled “The War of 1812 in Berwyn Heights – I Didn’t Know That!”

This talk will share some of the fascinating discoveries uncovered by the Bladensburg History Project – a community history collaboration launched as part of the bicentennial of the War of 1812. The area that is now Berwyn Heights was once considered part of greater Bladensburg, and the people who lived and worked here witnessed a great deal more than a disastrous defeat of the American forces in August 1814. Come and hear about what was happening “beyond the battle” in greater Bladensburg in the era of the War of 1812.

Doug McElrath is a special collections curator at the University of Maryland Libraries and is the research director for the Bladensburg History Project. He also is the Chair of Prince George’s Heritage, Inc., a group dedicated to historic preservation in the county.

WHAT’S IN A NAME ?

Washington Spa Spring & Gretta Railroad

Battery-powered car 11, ca 1910

(LeRoy O’King, Jr. Collection)

The Washington Spa Spring & Gretta Railroad (WSSGRR), the streetcar that came to Berwyn Heights in the 1910s, had one of the more memorable names of the many streetcar lines in the Washington area at the turn of the 20th century. But what does it signify? The key to the name, as might be expected, are the places connected by the streetcar.

Washington at 15th and H Street, NE near the old District boundary was one end point of the line. In addition to 15th and H Street, Maryland Avenue, Florida Avenue, Benning Road and Bladensburg Road converged here to form a big “starburst” intersection where passengers could transfer to other lines that went into the city center. At the time, the residents of East Washington felt they were under-served by the city’s street car system, and through their citizen associations strongly lobbied for better service and for a “cross-town line.” In February 1907, they got Congress to pass a law permitting WSSGRR to enter the District. Congressman Samuel S. Yoder, also a resident of East Washington and future President of WSSGRR, thanked the East Washington Citizen Association for supporting the bill and offered for WSSGRR to build the cross-town line.

Spa Spring refers to the Bladensburg Spa Spring located on the eastern bank of the Northeast Branch of the Anacostia River. In the 19th century, it was a popular tourist destination, and was visited by many for its alleged curative powers. An old Hopkins Atlas shows the location of the spring as well the concentration of businesses near it, including a Spa Spring Hotel.

Gretta refers to the homestead of Benjamin D. Stephen located east of Riverdale on the old Edmonston Road. Stephen was the Clerk of the Prince George’s Circuit Court at the time the streetcar was organized, and was elected as the first President of WSSGRR. Later, he conveyed Gretta to his oldest son Frank M. Stephen and two associates, who would plat the Gretta Addition to Riverdale, bounded on the west by the Eastern Branch, on the east by Edmonston Road, and in the south by Riverdale Road.

Berwyn Heights is notable for not being mentioned. A possible reason is that, in February 1905, when WSSGRR was incorporated in Maryland, it was not yet part of the plans. The certificate of incorporation describes the proposed streetcar route as “beginning at the District line, on the Baltimore and Washington Turnpike, where said line crosses the Pike at Colonel Reeve’s; then with the Pike through the Town of Bladensburg to the Edmonston Road; thence with said road or near thereto northerly to Gretta, a point on said road about one mile north of where the Riverdale Road leaves the Edmonston Road.” Berwyn Heights may have become a destination only after Yoder bought up properties in Berwyn Heights starting in late 1905 and became Vice President of WSSGRR, when the executive board was elected on April 2, 1907.

Sources:

Library of Congress historic newspapers online “Chronicling America”

Library of Congress “Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington…” Hopkins, 1879, p.28

City of Bladensburg website/history

Maryland State Archives “J.B.B. No. 1, Incorporations, 1901-1923”

LeRoy O’King, Jr. “100 Years of Capital Traction”

VETERANS DAY 2013

At its November 10 Veterans Day reception, the BHHC was pleased to honor Thomas Mutchler of 58th Avenue, a US Marine and World War II veteran. He fought in one of the the bloodiest battles of the Pacific campaign, the assault on the Japanese-held Island of Betio in the Tarawa Atoll, which took place November 20-23, 1943. PFC Mutchler was in the first wave of the amphibious assault, which required the Marines to wade ashore under heavy enemy fire because the water in the lagoon was not high enough for their amtracs to reach the beach. Former Councilmember Darald Lofgren arranged the ceremony, and Mayor Pro Tem James Wilkinson read a Proclamation on this 70th anniversary of the battle thanking Mr. Mutchler for his service.

Guests were also treated to an entertaining talk by freelance historian and archaeologist Patrick O’Neill from Virginia. O’Neill presented original research on the “Battle of the White House,” located at today’s Fort Belvoir, which took place September 13-15, 1814 during the War of 1812.

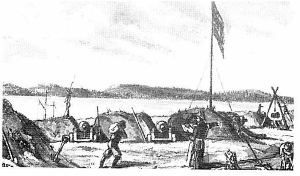

A squadron of 7 British war ships under the command of Captain James Gordon had sailed up the Potomac River to divert attention from the 5,000 British troops that were sailing up the Patuxent River at same time to attack Washington from the east. After defeating a band of Maryland and District militia at Bladensburg on August 24, the British reached the capital that same night, and, after being fired upon, burned all the public buildings.

Meanwhile, the Potomac squadron seized a large number of naval stores at Alexandria, which had surrendered to save their city. They set out on their return voyage with 21 prizes on September 2. Upon passing Fort Washington, they came under fire from Virginia militias, which turned into a pitched battle at White House landing. US Navy Captain David Porter had amassed 2,500 men on the bluff, and for 3 days fired mostly with muskets on the British ships that were held up by adverse winds. When the winds turned, the British nonetheless sailed away with all their ships, and met up with the Patuxent squadron in the Chesapeake Bay. It was at that point, according to O’Neill, the decision was made to attack Baltimore, where the decisive battle would be fought.

A SPOOKY TALE

There once lived a family at 8507 Cunningham Drive by the name of Hodges. They used to play cards with friends on weekends, and the friends had a son, who was believed to be possessed. – So says writer Mark Opsasnick in his captivating piece The Haunted Boy: The Cold Hard Facts Behind the Story that Inspired The Exorcist.

Opsasnick is a Greenbelter, born and raised, who specializes in “search-and-rescue missions down offbeat byways of the local past,” as David Montgomery of the Washington Post put it in a profile of the writer A Homer’s Odyssey. Opsasnick became interested in the story of the Exorcist in 1992 when he researched the life of famed blues-rock guitarist Roy Buchanan, who hails from Mount Rainier. The town, he says, was known for two things: the home of the great Roy Buchanan—and the alleged site of the story behind The Exorcist.

After spending hundreds of hours interviewing Mount Rainier’s old time residents, Opsasnick determined that the boy was actually not from Mount Rainier but from nearby Cottage City. Once refocused, his investigation of the haunted boy gathered steam as he was able to locate people who knew the family. From his interviews of former neighbors, friends and pastors, supported by meticulous research, a different story emerges than we know from the accounts published in newspapers, books and movies.

A ‘CHICKEN OR EGG’ QUESTION

On September 8, the Berwyn Heights Historical Committee visited the National Capital Trolley Museum in Colesville, MD, which preserves the history of DC’s electric streetcars.

Our group took a rambling ride on TTC (Toronto Transit Commission) car 4602 and received a presentation from docent Ken Rocker about the streetcars that served Berwyn Heights 100 years ago.

In August of 1910, the Washington Spa Spring & Gretta Railroad (WSSGRR) sent its first trolley from 15th and H Street, NE to Main and Water Street in Bladensburg. An extension to Berwyn Heights opened in the spring of 1912. This last streetcar company to be launched in the Capital area was troubled from the outset. Lawsuits were soon filed about schedules not kept; there were frequent breakdowns; and management changed within a couple of years of its opening. In October 1912, the name was changed to the Washington Interurban Railway. In May 1915, the Washington Interurban went into foreclosure, and in 1916, it was acquired by its rival, the Washington Railway & Electric Co.

In October 1912, the name was changed to the Washington Interurban Railway. In May 1915, the Washington Interurban went into foreclosure, and in 1916, it was acquired by its rival, the Washington Railway & Electric Co.

Mr. Rocker explained that WSSGRR was destined to have difficulties because it had to compete with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the already well-established streetcar line of the City & Suburban, later bought by the Washington Railway & Electric, running to Laurel via Hyattsville, College Park and Berwyn. There simply were not enough people living in this area at the time, he said, to generate sufficient demand for a 3rd line. This was certainly true for Berwyn Heights, which had no more than a few dozen homes when WSSGRR started to operate. But the line also served East Riverdale, which was going through a growth spurt, and the old trading center, Bladensburg.

Seen from a different angle, the entrepreneurs who invested in this streetcar line, did so to spur development of the communities east of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. They had purchased real estate along the right-of-way and established real estate companies to induce D.C. residents to move to the suburbs. This had worked with some of the other streetcar companies operating in and around Washington. One might ask what comes first: development or transportation?

HEINIE MILLER – BOXING RENAISSANCE MAN

At the start of the school year of 1936-1937, Harvey L. “Heinie” Miller (1888 – 1967) was hired as head coach of the varsity boxing squad and professor of journalism by the University of Maryland, College Park. Miller was the right man for the job. He knew every aspect of the sport from personal experience and had spent 20 years writing about it. He put his stamp on the boxing program that same year: the team won the Southern Conference championship, and team boxer Ben Alperstein won the lightweight title in the National Inter-Collegiates. Under Miller’s direction, the terrapin tappers would twice more capture the Southern Conference title.

Miller was no stranger to the neighborhood. He had been involved with the Sportland boxing ring that opened in Berwyn Heights in 1922. At the time, boxing was illegal in the District of Columbia, and the action took place in nearby suburbs in Maryland and Virginia. At Sportland, Miller initially was a referee and, in 1923, became the matchmaker. He staged several high-profile shows before Berwyn Heights Town commissioners clamped down on the entertainment. Among the star performers boxing under Miller’s promotion, was young Goldie Ahearn of Washington D.C., who would go on to become a nationally known boxer and promoter himself.

When the Sportland arena ran into difficulties obtaining permits for boxing shows, Miller promoted at Kenilworth Arena that opened in 1924. The boxing arenas stirred up a considerable amount of controversy in the still half-rural communities where they were located. The fights drew a lot of city folk that did not always behave in an exemplary manner. Berwyn Heights residents Jean McConnell and Jerry Anzulovic, who grew up in Berwyn Heights in the 1930s and 40s, remember hearing stories about “more fights taking place outside the arena than inside,” and “marshals regularly being called in to keep the peace.”

Reportedly, Kenilworth arena even was the target of a robbery by the notorious Candy Kid Gang of Baltimore. Miller told the Evening Star, when he was promoting at Kenilworth, he was tipped off by an anonymous caller about the planned robbery. So, he brought in a handful of battle-hardened Marines who, armed with sawed-off shot guns, guarded the box office on the night of the show. Residents, churches and women’s groups fought back by petitioning their Town and County Commissioners to stop the ‘brutal contests’ and withhold licenses.

Miller’s love affair with boxing started early. He began to box in staged fights at age 12 in a barn loft at North Avenue and 25th Street in his native Milwaukee. At age 17, he abandoned his theological studies at Concordia Lutheran College, and in 1905 joined the Navy. His training as a sailor took place on the frigate U.S.S. Constellation, now anchored in Baltimore Harbor as a museum.

Miller then was assigned to the U.S.S. Wilmington, where he had ample opportunity to box and refine his craft. He won the all-service bantam championship in 1906, and the Far East featherweight title in 1907. But his greatest achievement was winning the Far East lightweight title in 1908 against the Australian Jimmy Dwyer. The fight was featured in a Ripley’s “Believe It or Not” cartoon because Miller scored an improbable knockout in the 13th round after being floored 13 times in the first four rounds.

In 1921, Miller retired from the Navy and settled in Washington, D.C. He worked as an editor for Our Navy magazine, sports writer for the Washington Herald and publisher of the Coast Guard Magazine. He also organized the 5th Marine Reserve Battalion of the District of Columbia, and he promoted boxers at Sportland and Kenilworth Arena.

In 1934, boxing was finally legalized in the District, and the now legitimate sport was overseen by the new D.C. Boxing Commission. Heinie Miller was selected as its first chairman. When the D.C. Commission affiliated with the National Boxing Association, he quickly rose through the ranks of that organization and became President in 1939. To these responsibilities he added the coaching/teaching position at UMD in 1936.

In 1940, Colonel Miller took a leave of absence to return to active military duty. During World War II, he served in the Pacific with the 5th Marine Reserve Battalion with which he was still closely affiliated. After the war, he resumed his positions at the University of Maryland and the D.C. and National Boxing Commissions. In 1948, he was called upon to serve a stint as treasurer of the U.S. Olympic Boxing Committee. Miller continued to coach and write about boxing into the late 1950s. He died from pneumonia on December 26, 1967, survived by his daughter Lucilee Bernard, a grand-daughter and 2 great grand-children.

Sources:

Sportland Boxing Ring flyer, BHHC 2013

University of Maryland Yearbook, 1937, p. 132

The Truth About Boxing, Harvey L. Miller, 1951, Introduction, Lewis F. Achison

Ring Career Began after Attempt at Theology, Lewis F. Atchison,

Evening Star, 1-28-1940

Newspaper articles from The Washington Post (posted at BHHC dropbox)

Newspaper articles from The Washington Times, Evening Star

(available at Chronicling America )

Author: Kerstin Harper

SPORTLAND MARKER DEDICATED

By 11 am on a bright May 4th, 2013, the Historical Committee’s tent was set up for Berwyn Heights Day. Posters, brochures and the mockup of the Sportland Boxing Ring marker were on display. Many visitors stopped in, including some former residents.

Maria Snoddy, Daughter Laura Collier, and BHHC Chair Sharmila Bhatia with Sportland marker, May 4, 2013

The BHHC was very pleased that Maria Snoddy, who grew up in Berwyn Heights and now lives in Greenbelt, accepted an invitation to attend the Sportland marker dedication ceremony. Mrs. Snoddy is a grand-daughter of the former owners of the boxing arena, John O. and Maria Waters. She made the trip despite being in a wheelchair, accompanied by her daughter Laura Collier.

Talking with Sharmila Bhatia, Mrs. Snoddy recalled that her grandfather was quite a character. He tried his hands on many things. On the Sportland property, there were grape arbors and from the grapes Waters made his own wine. He hired men from Lakeland (now Lake Artemesia park) to help him work his large garden.

Mrs. Snoddy also shared some interesting facts about her own parents, Ned and Edna Waters. The home they built next to Sportland on 60th Avenue has floor trusses that came from FDR’s inauguration stand. The lumber was sold as scrap at Hechinger’s. Waters knew the lumber was coming into the store and made arrangements to purchase it.

Ned Waters was elected to the County Council in 1950 and served for one term. His name and those of the other council members who served at the time, were memorialized on a plaque installed on the Woodrow Wilson bridge, when it was built. The plaque, however, was removed during the recent reconstruction.